The Great AMAD Archive Absurdity

While Redline was busy spooling

up the flux capacitor to bring our website design into the 21st century, we

kind of missed a pretty damn important story: Israel's daring raid on a Tehran

warehouse to steal tonnes of archival documents relating to Iran's former

nuclear weapons program. Yes, we know - it was perhaps the best story of the

past five years or so when it comes to open source information about Iran's

weapons-related activities. We apologise! Web design is not fun.

Anyway, by now you've almost

certainly heard the broad outlines of what happened. On 31 January last year,

Israel's intelligence services pulled off the kind of coup that spies dream

about - a silent nighttime raid on a secret, secured warehouse and the

subsequent spiriting away of more than 30,000 documents relating to Iran's

covert nuclear-related programs and research. As you can read in any of the excellent accounts

of the Israeli operation, the haul from the archives included such gems as:

- documents containing design

information for a nuclear weapon.

- documentation of Iran's

ultimate goal of the pre-2003 nuclear weapons program.

- information on experiments to

make a uranium metal compound, uranium deuteride, for use as a neutron initiator

to spark nuclear explosions.

- details of various tests and

experiments relating to nuclear weapon design.

For more details on just what was

uncovered in these archives, we recommend reading the work of the Institute for Science and International Security,

who have a selection of the original documents.

But that's the gory details. Here

are our big picture takeaways from the archive story.

1. SPND's security is

really, really terrible.

The fact that all of the most

sensitive documents relating to Iran's secret nuclear activities were kept in a

poorly-secured warehouse is an absolutely damning indictment on Tehran's

operational security, and must have come to a shock to many elements of the

Iranian government. Iran's own foreign ministry, probably blindsided by the

revelation of the archival documents, was forced to come out with this gem of a subsequent statement to the press:

"the notion that Iran would abandon any kind of sensitive information in

some random warehouse in Tehran is laughably absurd".

Indeed, it is laughably absurd

that Iran would leave its most precious nuclear documents open to theft - but

it's true nonetheless. And if you've been reading this blog, you'll know well

that this is certainly not the first time that the Iranian nuclear or missile

programs have been involved in laughably absurd security breaches.

Who was responsible for this one?

There's a couple of organisations in Iran for whom the words

"security" and "laughably absurd" go together like gin and

tonic - first, the IRGC, and second, the Ministry of Defence's Organisation for

Defensive Innovation and Research, a.k.a. SPND. Each of these organisations has bumbled from security blunder to

security blunder - and it has only taken a five-dollar blog like ours to find

that out.

The loss of the nuclear archive,

for once, wasn't an IRGC bungle. Redline has learned from our sources that it was actually SPND who was responsible for managing the security of the archive material - and, consequently, the massive security failure and

embarrassment that was caused by the security breach there. Frankly, a ten

year-old Macauley Culkin would have done a better job of securing the place.

2. See point

#1.

SPND IS REALLY BAD AT SECURITY!

3. There are plenty more Amad

program alumni still in positions of power in Iran.

The various reports on the

nuclear archive by the Institute for Science and International Security do a

nice job of reminding us that several members of Iran's current leadership,

including president Hassan Rouhani and secretary of Iran's Supreme National

Security Council, Ali Shamkhani, were involved in the original cover-up of

Iran's pre-2003 nuclear weapons program, including leading a campaign of

deception and obfuscation against the international nuclear watchdog, the IAEA.

What the documents from the

warehouse also confirm is that at lower levels, there are still lots of alumni

of the Amad program - the Iranian name for the pre-2003 nuclear weapons

effort - in important roles in Iran's science and technology scene.

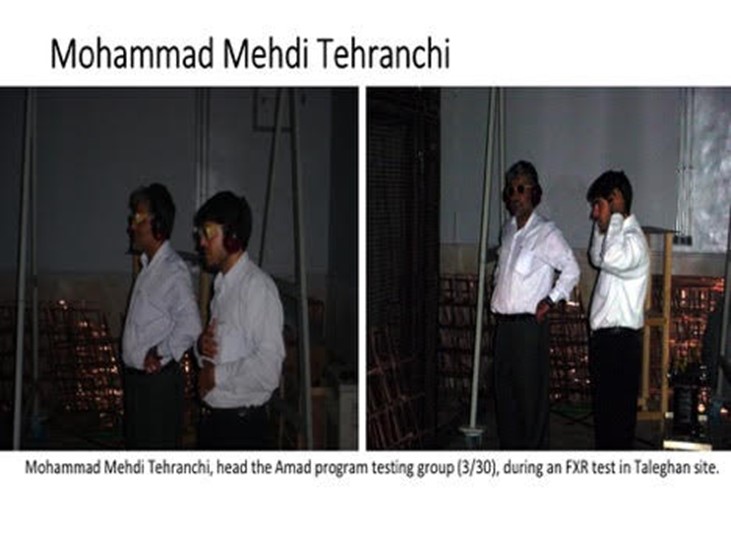

Take Mohammad Mehdi Tehranchi (محمد مهدی طهرانچی), currently a professor of physics at Iran's Shahid Beheshti University, one

of the country's premier science institutions. The archives have a lovely set of photos

of a youthful Mr. Tehranchi watching over tests of something called a flash

x-ray machine, something that is used to test whether an implosion mechanism in

a nuclear weapon is working properly.

The archives are full of other

names of people like Tehranchi who've gone on to lead relatively distinguished

careers in science and technology while covering up the fact that they spent

the turn of the millennium trying as quickly as possible to make nuclear

weapons. Seyed Mohammad Mehdi Hadavi (سید محمد مهدی هادوی) is another - we've

written about him before, and

sure enough he pops up in the archives

lobbying to keep aspects of the Amad program underway despite the Iranian

leadership's September 2003 order to halt it. He's now an associate (ouch)

professor at Tarbiat Modares University, happily appearing in photos holding

things that don't look at all like neutron initiators.

The archives are full of other

names of people like Tehranchi who've gone on to lead relatively distinguished

careers in science and technology while covering up the fact that they spent

the turn of the millennium trying as quickly as possible to make nuclear

weapons. Seyed Mohammad Mehdi Hadavi (سید محمد مهدی هادوی) is another - we've

written about him before, and

sure enough he pops up in the archives

lobbying to keep aspects of the Amad program underway despite the Iranian

leadership's September 2003 order to halt it. He's now an associate (ouch)

professor at Tarbiat Modares University, happily appearing in photos holding

things that don't look at all like neutron initiators.

4. Mohsen Fakhrizadeh

has an amazing talent for bureaucratic survival.

One Amad alumnus who hasn't been

able to let the nuclear weapons dream go and move on to a blissful academic

career of advising pretty young engineering undergrads is Mohsen Fakhrizadeh

(محسن فخریزاده), the so-called Robert Oppenheimer of

Iran's pre-2003 nuclear weapons program.

If nothing else, Fakhrizadeh is a

survivor: he has been in a position of authority over Iran's nuclear

weapon-related activities - overt, clandestine, and dual-use - for more than

thirty years now. Fakhrizadeh led the Amad project from the late 1990s until

2003. At the closure of Amad, he was appointed to lead the project's successor

organisation, known as SDAAT, that aimed to keep together the skills and

knowledge accumulated during the weapons effort. Since about 2010, he's headed

SPND, although it hasn't exactly blossomed as a technology powerhouse.

Thirty years is a very long time

to hold a job. And even more so when one isn't particularly successful at it.

You will note during this thirty years, a) Iran has never managed to make

nuclear weapons, and b) has failed completely, time and again, to keep secret

its efforts at playing to the edge of what constitutes nuclear weapons

development.

What's even worse is the huge cost and corruption of the programs that Fakrizadeh has administered. We're all in favor of a bit of nepotism here at Redline but over the last thirty years, exorbitant sums have managed to find their way into the pockets of Fakrizadeh's sons, Hani Hamed and Hadi, as well as other corrupt officials in SPND.

What's even worse is the huge cost and corruption of the programs that Fakrizadeh has administered. We're all in favor of a bit of nepotism here at Redline but over the last thirty years, exorbitant sums have managed to find their way into the pockets of Fakrizadeh's sons, Hani Hamed and Hadi, as well as other corrupt officials in SPND.

We're starting to think that

maybe Fakhrizadeh is the best thing to happen to global non-proliferation

efforts against Iran. Long may his failures continue!

5. Stay tuned to

Redline.

We don't think that our modest

blog features in the warehouse archives, so forgive us for this slight misuse

of listicle number five.

The warehouse in Tehran has given

analysts more than enough fodder to chew on with respect to Iran's historic

nuclear weapon-related activities. But if you want to know what's happening

today, keep reading us. We've got some good insights coming up on covert

aspects of Iran's current nuclear and missile programs, ongoing IRGC

shenanigans abroad, and other stuff that Tehran doesn't want you to know about.

Comments

Post a Comment